Foundation of Carmel in the United States

Historical Roots

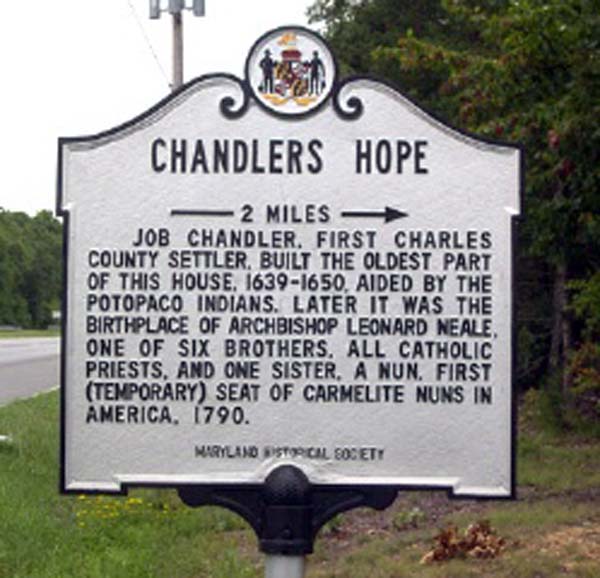

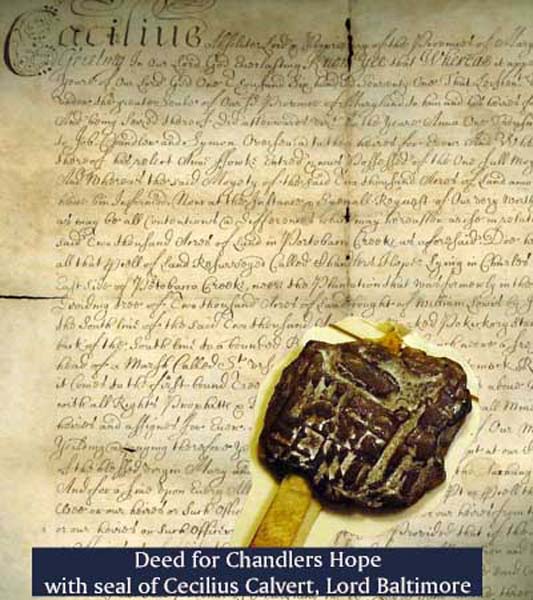

On April 19, 1790, four Carmelite nuns embarked from Hoogstraet, Belgium, for Charles County, Maryland, in the newly formed United States of America. The nuns were members of English-speaking communities in Hoogstraet and Antwerp, important centers for the English recusant community of the Lowlands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. All but one of the nuns were natives of Maryland descended from the Catholic gentry reaching back to the beginning of Lord Baltimore’s colony. Accompanied by their Maryland-born, Jesuit trained chaplain, they arrived at Brent’s Landing on the Potomac River July 11, the same year John Carroll was ordained first Bishop of the United States. On July 21, 1790, the nuns established the first community of religious women in the thirteen original states, the first Carmelite Monastery in North America.

The Carmelite Order

The Carmelite Order they were establishing in the new world had weathered nearly six centuries of existence since its eremitical beginnings on Mount Carmel in Palestine at the dawn of the thirteenth century.1 Carmelite friars had migrated to Europe and joined the great mendicant surge; they had moved into the city and the university, setting up an uneasy tension between contemplation and apostolic ministry that has endured for over eight hundred years.2 The long affiliation of women with the Order had been formally recognized in 1452 when the beguines of “Ten Elsen” in Guelders were received into the Order by John Soreth, the General.3

In 1562 during the Counter Reformation, Teresa of Avila had initiated in Spain the reform of both the nuns and the friars. During her life time, in an expansion marked by extreme conflict, seventeen convents of Carmelite nuns had been founded throughout Spain setting the stage for the separation of the Carmelites into two distinct Orders by 1593.4 When Teresa died in 1582, she left in the post-Tridentine Church not only a way of life characterized by contemplative prayer and intense community but also a deep conviction about the place of contemplative love and communion in the transformation of the world. Together with John of the Cross, her companion in reforming the friars, she bequeathed to Carmelites and to Christianity a legacy of mystical texts bearing extraordinary witness to the experience of God in human life. These classic texts have not only inspired Teresian Carmelite life for almost five hundred years but they have also encouraged and motivated countless spiritual seekers.

In 1562 during the Counter Reformation, Teresa of Avila had initiated in Spain the reform of both the nuns and the friars. During her life time, in an expansion marked by extreme conflict, seventeen convents of Carmelite nuns had been founded throughout Spain setting the stage for the separation of the Carmelites into two distinct Orders by 1593.4 When Teresa died in 1582, she left in the post-Tridentine Church not only a way of life characterized by contemplative prayer and intense community but also a deep conviction about the place of contemplative love and communion in the transformation of the world. Together with John of the Cross, her companion in reforming the friars, she bequeathed to Carmelites and to Christianity a legacy of mystical texts bearing extraordinary witness to the experience of God in human life. These classic texts have not only inspired Teresian Carmelite life for almost five hundred years but they have also encouraged and motivated countless spiritual seekers.

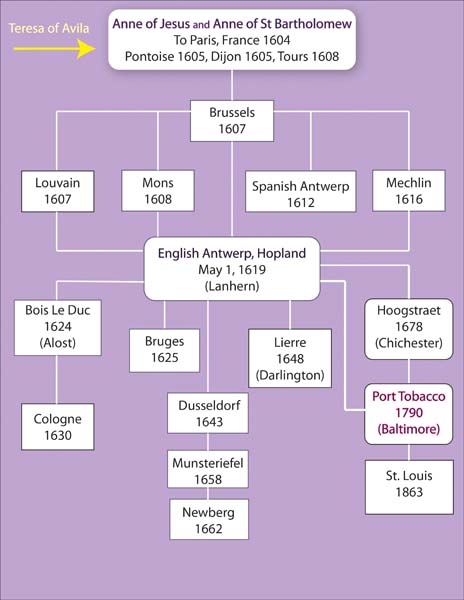

It was the disciples of St. Teresa, Anne of Jesus (Lobera) and Anne of St. Bartholomew (Garcia), who carried the Teresian tradition to the Low Countries and the Continent. They founded monasteries in Paris (1604), Pontoise (1605), Dijon (1605) and Tours (1608). By 1607, “the Spanish Mothers” had moved into the Spanish Netherlands to found “the Royal Convent” in Brussels followed in quick succession by foundations in Mons (1608), Louvain (1607), Antwerp (1612) and Mechlin (1616). From these houses in the Low Countries, the English-speaking Carmel in Antwerp was established in 1619 under the leadership of Anne of the Ascension (Worsley, 1588-1644).5 To this monastery, which had the character of a motherhouse, and to its two English-speaking daughter houses of Lierre (1648) and Hoogstraet (1678), came women from recusant families in England and the Lowlands.6 Many of these families had forfeited property and wealth to practice their religion freely in the Low Countries. Others, to remain Catholics, had risked imprisonment and even death in their native England. The English-speaking Carmelites by inheritance, therefore, prized liberty of conscience and freedom of religion.

It was the disciples of St. Teresa, Anne of Jesus (Lobera) and Anne of St. Bartholomew (Garcia), who carried the Teresian tradition to the Low Countries and the Continent. They founded monasteries in Paris (1604), Pontoise (1605), Dijon (1605) and Tours (1608). By 1607, “the Spanish Mothers” had moved into the Spanish Netherlands to found “the Royal Convent” in Brussels followed in quick succession by foundations in Mons (1608), Louvain (1607), Antwerp (1612) and Mechlin (1616). From these houses in the Low Countries, the English-speaking Carmel in Antwerp was established in 1619 under the leadership of Anne of the Ascension (Worsley, 1588-1644).5 To this monastery, which had the character of a motherhouse, and to its two English-speaking daughter houses of Lierre (1648) and Hoogstraet (1678), came women from recusant families in England and the Lowlands.6 Many of these families had forfeited property and wealth to practice their religion freely in the Low Countries. Others, to remain Catholics, had risked imprisonment and even death in their native England. The English-speaking Carmelites by inheritance, therefore, prized liberty of conscience and freedom of religion.

American Carmelites

British colonials from Maryland began crossing the ocean to become Carmelites in 1742.7 Among them were Mary Brent (1731-1784) who joined the Antwerp community in 1751; and Anne Matthews (1732-1800) who three years later together with Ann Hill (1734-1813), the cousin of John Carroll, entered the community in Hoogstraet.8 By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, therefore, the seed for Carmel in America had taken root and produced strong American leadership for the “English Teresians” in both Hoogstraet and Antwerp. This leadership proved to be a strong base from which to plan for the founding of a new monastery in Maryland. Mother Margaret Mary Brent had the primary role in preparing for this foundation. When she died in 1784 at age fifty-three just after completing six years as prioress of the Antwerp community, it fell to her close collaborator, Mother Bernardina Matthews, a neighbor from Charles County who was prioress at Hoogstraet Carmel from 1771 to 1790, to take on the task of leading the first Carmelite foundation to their native Maryland. Through Mother Bernardina the tradition of both colonial Maryland Catholicism and Carmelite life and spirituality would be passed to a new generation.

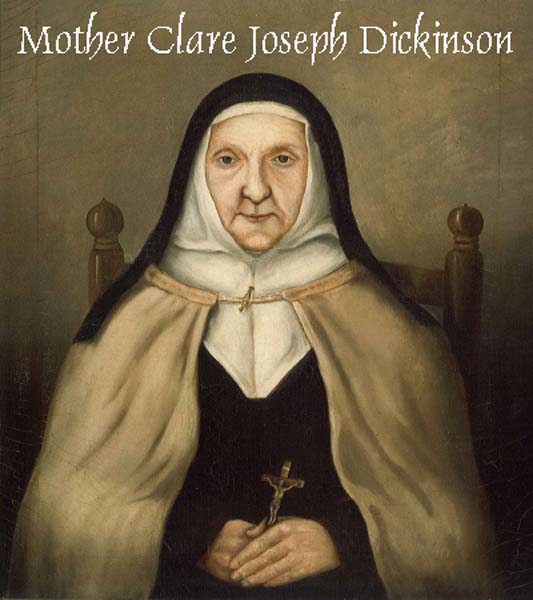

Accompanying Bernardina Matthews on the foundation voyage were her two nieces, Sister Mary Eleanora (Susanna Matthews) and Sr. Mary Aloysia (Ann Teresa Matthews), who had entered the Hoogstraet Carmel following the close of the Revolutionary War, and an Antwerp Carmelite, Sister Clare Joseph Dickinson, a native of London, who became prioress of the new monastery in 1800 on the death of Bernardina. She was chosen to replace Mary Margaret Brent by Father Charles Neale, the Jesuit-trained chaplain of Antwerp Carmel. Neale was the final member of the founding party. Born into the Maryland gentry, a novice at the time of the Jesuit suppression, he was bonded by family ties to each of the Maryland women connected with the foundation and was revered by the first generation of American Carmelites as a founder and father.

Accompanying Bernardina Matthews on the foundation voyage were her two nieces, Sister Mary Eleanora (Susanna Matthews) and Sr. Mary Aloysia (Ann Teresa Matthews), who had entered the Hoogstraet Carmel following the close of the Revolutionary War, and an Antwerp Carmelite, Sister Clare Joseph Dickinson, a native of London, who became prioress of the new monastery in 1800 on the death of Bernardina. She was chosen to replace Mary Margaret Brent by Father Charles Neale, the Jesuit-trained chaplain of Antwerp Carmel. Neale was the final member of the founding party. Born into the Maryland gentry, a novice at the time of the Jesuit suppression, he was bonded by family ties to each of the Maryland women connected with the foundation and was revered by the first generation of American Carmelites as a founder and father.

Just as the Maryland Catholic gentry were bound together by complex and multiple family ties, so were the founders of Carmel in America. One of the characteristics of the community they established in Port Tobacco was the bondedness created by multiple family ties, not only among the founders but also among the Maryland women who entered the community after its foundation in 1790.9 These blood relationships, often considered hazardous in religious communities in the more recent past, probably stabilized the new community and contributed to its success, its sense of presence to the surrounding community and the early Church, and its determination and ability to survive.

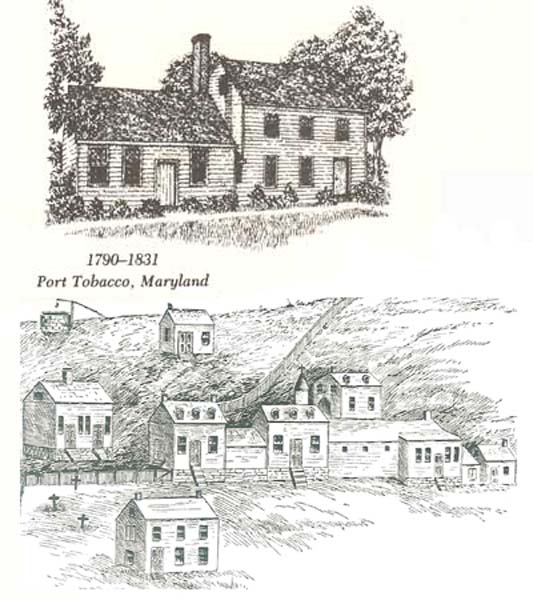

The First Forty Years: Port Tobacco

The first American Carmelites established their monastery on a farm at Port Tobacco in Southern Maryland and dedicated it on October 15, 1790 to the Sacred Hearts of Jesus, Mary and Joseph. (For theological reasons, this was very soon abbreviated to the Sacred Heart.) Managed by their chaplain, Charles Neale, who donated his entire patrimony to buy it, the farm supported the Anglo-American community in their poor and simple life for forty years. There were significant characteristics of this first Carmelite foundation, the only one in the United States for 73 years, that were influential in shaping the future.

The first American Carmelites established their monastery on a farm at Port Tobacco in Southern Maryland and dedicated it on October 15, 1790 to the Sacred Hearts of Jesus, Mary and Joseph. (For theological reasons, this was very soon abbreviated to the Sacred Heart.) Managed by their chaplain, Charles Neale, who donated his entire patrimony to buy it, the farm supported the Anglo-American community in their poor and simple life for forty years. There were significant characteristics of this first Carmelite foundation, the only one in the United States for 73 years, that were influential in shaping the future.

First, the community was rooted in the Anglo-Catholic tradition that prized the values of religious toleration, mutual respect and freedom of conscience. The Maryland gentry carried in their collective soul the memory of a colony founded on the principles of religious toleration and mutual respect. Just as deep, however, was the later memory of disenfranchisement, deprivation of religious liberty and exclusion from public service effected by the penal laws. Even though Maryland Catholics did not suffer the loss of their wealth or social position, they did suffer the disgrace of second-class citizenship. Liberty of conscience, therefore, was a crucial value in shaping their self-understanding and their relationship with God and others, just as it was for the English Teresians for somewhat different reasons.10

First, the community was rooted in the Anglo-Catholic tradition that prized the values of religious toleration, mutual respect and freedom of conscience. The Maryland gentry carried in their collective soul the memory of a colony founded on the principles of religious toleration and mutual respect. Just as deep, however, was the later memory of disenfranchisement, deprivation of religious liberty and exclusion from public service effected by the penal laws. Even though Maryland Catholics did not suffer the loss of their wealth or social position, they did suffer the disgrace of second-class citizenship. Liberty of conscience, therefore, was a crucial value in shaping their self-understanding and their relationship with God and others, just as it was for the English Teresians for somewhat different reasons.10

Second, in their spirituality, the American foundresses stood within the moderate humanistic French school as it was mediated to them through the English Jesuit inheritance in Maryland and the Lowlands and the central elements of Teresian Carmelite spirituality brought to the Low Countries in 1607 by the successors of Teresa of Avila, Anne of Jesus and Anne of St. Bartholomew. Although the Americans stressed the profound experience of contemplative prayer with a strong emphasis on the humanity of Christ, they were, according to historian Joseph Chinnici, the inheritors of a “muted mysticism” and a practical, restrained, dignified piety. Grounded in deep respect for the movement of the Holy Spirit in each person, a position basic to the understanding and experience of contemplation, their spirituality correlated well with their inherited position of political liberty and rights of conscience.

Second, in their spirituality, the American foundresses stood within the moderate humanistic French school as it was mediated to them through the English Jesuit inheritance in Maryland and the Lowlands and the central elements of Teresian Carmelite spirituality brought to the Low Countries in 1607 by the successors of Teresa of Avila, Anne of Jesus and Anne of St. Bartholomew. Although the Americans stressed the profound experience of contemplative prayer with a strong emphasis on the humanity of Christ, they were, according to historian Joseph Chinnici, the inheritors of a “muted mysticism” and a practical, restrained, dignified piety. Grounded in deep respect for the movement of the Holy Spirit in each person, a position basic to the understanding and experience of contemplation, their spirituality correlated well with their inherited position of political liberty and rights of conscience.

Third, a second strand of spirituality coexisted in the beginning. A leaning toward the more rigoristic French school present in Charles Neale and Clare Joseph Dickinson evidenced suspicion of the emotions/passions/will and stressed rational control, mortification, obedience to the rule, the superior and regularity of life.

Fourth, from the beginning of the American foundation, a level of culture and intellectual life, characteristic of both the Maryland Catholic gentry and the English Teresians was encouraged, as is confirmed by the extensive library brought on their 1790 ocean voyage to America by the foundresses.

Fifth, central to their contemplative prayer ministry were the nuns’ close bonds with the Jesuits, many of whom came from the same families as the sisters, the French Sulpicians establishing the first seminary in the United States, all the first Bishops in the country beginning with John Carroll, and the various founders and members of religious communities, including Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton.

The Move to Baltimore

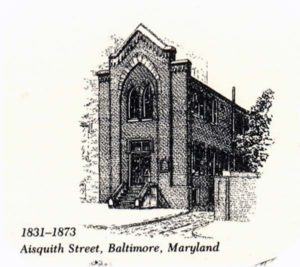

Following the death of the two founding prioresses and driven by the economically depressed condition of Charles County, the death of Charles Neale and the failure of the farm, the community closed the monastery at Port Tobacco and moved to Aisquith Street in East Baltimore in 1831. (See separate entry for the history of the monastery property in Port Tobacco.) To support themselves at a time when begging had “become very odious to the Catholics of the city,” they opened in October 1832 The Carmelite Sisters Academy for the Education of Young Ladies of all religious denominations, one of the first four such academies in the original States. For twenty years, three or four of the nuns, Sister Teresa (Juliana Sewall) chief among them, staffed the school. Although in 1792 Bishop John Carroll had, in view of his need for teachers, obtained a rescript from the Cardinal Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith allowing the nuns to teach, they had refused Carroll’s request believing it was contrary to their contemplative charism. When the survival of their contemplative life depended upon it, however, they accepted “the full confirmation of the dispensation for teaching” secured by Archbishop James Whitfield. The school was one historical manifestation of the enduring tension between contemplative prayer and apostolic ministry that has characterized the Carmelite Order since the early movement from eremitical beginnings on Mount Carmel to mendicant status and ministry in European urban centers. In 1851, when the nuns could survive financially without it, the school was closed.

Following the death of the two founding prioresses and driven by the economically depressed condition of Charles County, the death of Charles Neale and the failure of the farm, the community closed the monastery at Port Tobacco and moved to Aisquith Street in East Baltimore in 1831. (See separate entry for the history of the monastery property in Port Tobacco.) To support themselves at a time when begging had “become very odious to the Catholics of the city,” they opened in October 1832 The Carmelite Sisters Academy for the Education of Young Ladies of all religious denominations, one of the first four such academies in the original States. For twenty years, three or four of the nuns, Sister Teresa (Juliana Sewall) chief among them, staffed the school. Although in 1792 Bishop John Carroll had, in view of his need for teachers, obtained a rescript from the Cardinal Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith allowing the nuns to teach, they had refused Carroll’s request believing it was contrary to their contemplative charism. When the survival of their contemplative life depended upon it, however, they accepted “the full confirmation of the dispensation for teaching” secured by Archbishop James Whitfield. The school was one historical manifestation of the enduring tension between contemplative prayer and apostolic ministry that has characterized the Carmelite Order since the early movement from eremitical beginnings on Mount Carmel to mendicant status and ministry in European urban centers. In 1851, when the nuns could survive financially without it, the school was closed.

1873-present

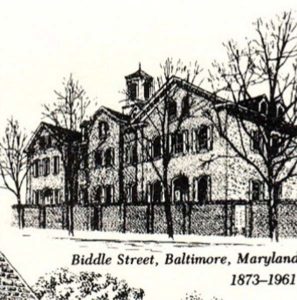

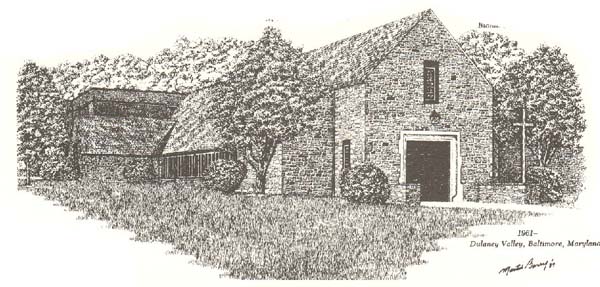

In 1873, the community relocated a second time to a newly built monastery on Caroline and Biddle Streets in East Baltimore where they remained for almost one hundred years. In 1961, shortly before Vatican II, the community moved to a twenty-seven acre property in Dulaney Valley, Baltimore County. This relocation and dislocation after a century in one place proved to be a significant preparation for the process of renewal begun by the Council. In 1990, Baltimore Carmel observed its bicentennial with celebratory liturgies and a weeklong seminar, Carmel and the Rediscovery of the American Soul, which was attended by eight hundred participants – Carmelites, religious and lay people. In the year 2015, during the fifth centenary of St. Teresa’s birth, the community marked 225 years of continuous Carmelite life in Maryland.

In 1873, the community relocated a second time to a newly built monastery on Caroline and Biddle Streets in East Baltimore where they remained for almost one hundred years. In 1961, shortly before Vatican II, the community moved to a twenty-seven acre property in Dulaney Valley, Baltimore County. This relocation and dislocation after a century in one place proved to be a significant preparation for the process of renewal begun by the Council. In 1990, Baltimore Carmel observed its bicentennial with celebratory liturgies and a weeklong seminar, Carmel and the Rediscovery of the American Soul, which was attended by eight hundred participants – Carmelites, religious and lay people. In the year 2015, during the fifth centenary of St. Teresa’s birth, the community marked 225 years of continuous Carmelite life in Maryland.

Foundations

Seven branches sprouting forty-seven foundations were to grow on the initial Baltimore tree. The second Carmel in the country was founded in St. Louis on October 1, 1863 at the invitation of Archbishop Peter R. Kenrick and with the encouragement of Francis P. Kenrick, Archbishop of Baltimore. A sad peculiarity of this foundation, made during the Civil War, was that a period of community conflict and unrest was resolved when the five foundresses, led by Mother Gabriel (Ellie Boland) and Mother Alberta (Mary Jane Smith) departed Baltimore. Only fourteen years later St. Louis Carmel sent four nuns, led by Mother Teresa (Louise Josephine Roman) to establish New Orleans Carmel, the third in the United States and the first of eleven monasteries founded on the St. Louis branch between 1877 and 1955.

With the exception of Saint Louis Carmel, which was founded from the Aisquith Street monastery, all Baltimore Carmel’s foundations were made not from Port Tobacco nor Aisquith Street, but from the Biddle Street monastery. In 1890, the fourth branch of fourteen monasteries began to grow (1890-1965) when the fourth Carmel was founded in Boston with the wise, experienced leadership of Mother Beatrix (Josephine Majers). She had been a student in the Carmelite Academy. Among her four companions from Baltimore were two future foundresses: Sister Gertrude (McMaster), the founding prioress of Philadelphia Carmel in 1902 and Sister Augustine (Eulalia Tucherman), a native Bostonian who led the foundation to Santa Clara in 1908.

Foundresses left Baltimore for: Brooklyn in 1907 – Mother Teresa (Pauline McMaster); Seattle in 1908 – Mother Raphael (Louise Keating) and Sister Cyril (Annie McDougal); Davenport, Iowa in 1911 – Mother Clare (Mary Elizabeth Nagle) and Mother Aloysius (Anna Heiker); Wheeling, West Virginia in 1913 – Mother Joanna (Josephine Sneeringer), Sister Mary Magdalen (Francis Potts) and Sister Teresa (Potts); New York City in 1920 – Mother Teresa (Cawley) and Mother Agnes (Garvin). These five branches account for twenty foundations made throughout the U.S. from 1907-1961, twelve post World War II.

Historical Documents & Artifacts >>

Notes

- The Carmelite Rule was written sometime between 1206 and 1214 by Albert of Vercelli, the Patriarch of Jerusalem. Although he was most certainly setting down a way of life already lived for some time by western hermits on Mount Carmel, it is only in the thirteenth century that indisputable evidence of their presence there exists.

- See Joachim Smet, O.Carm., The Carmelites, A History of the Brothers of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, vol. 1 (Rome: Carmelite Institute, 1975); Elias Friedman, O.C.D., The Hermits of Mount Carmel, A Study in Carmelite Origins (Rome: Teresianum, 1979); Carlo Cicconetti, O.Carm., The Rule of Carmel (Darien, Illinois: Carmelite Spiritual Center, 1984).

- This gradual affiliation over two centuries is detailed by Joachim Smet in Cloistered Carmel (Rome: Institutum Carmelitanum, 1986) and in Smet, The Carmelites, vol. 1, pp. 103-116.

- Today there are two Carmelite Orders: the Carmelites of the Ancient Observance and the Discalced Carmelites.

- While Anne Worsley came from the Mechlin monastery and had been trained by both Anne of Jesus (Brussels monastery) and Anne of St. Bartholomew (Spanish Antwerp monastery), Margaret Baston and Anne Duynes came from Brussels, Clare Laithwaite from Louvain and Teresa Ward from Mons. Teresa Ward, who dressed as a man to leave England, was the sister of the indomitable Mary Ward (1585-1645) who founded in 1609 the first community of unenclosed women religious, the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

- For example, Rose Fisher, St. John Fisher’s grand-niece was professed in Antwerp in 1636 and Lady Anne Somerset, “daughter of the most illustrious Henry Earl Marquess of Worcester of the royal family of Plantagenet” in 1643. Although Anne Worsley’s paternal great grandfather, Sir James Worsley, was a page of Henry VIII, Keeper of Lions in the Tower, Groom of Robes and Governor of the Island of Wight, her father disobeyed Queen Elizabeth’s order in 1560 to return to England and therefore lost all property under the recusancy laws. Her maternal great grandfather, Sir Nicholas Hervey, a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber to Henry VIII, was present with Thomas More at Andres in 1520. During Elizabeth’s reign, Anne’s grandfather, Thomas Hervey, went abroad to Spain and then to the Spanish Netherlands because of his religion. See Anne Hardman, SND, English Carmelites in Penal Times (London: Burns Oates and Washbourne, 1936), pp. 79-80, 59-60, 136-40.

- The first native of Maryland to become a nun was Mary Digges who was a canoness regular of the Holy Sepulchre at Liege as early as 1721. She was Mary Margaret Brent’s aunt. See Brent letter to “My dearest Cousin” (Charles Neale or one of his two priest brothers) written around 1776: “I suppose you have heard of Aunt Mary Digges death, long ago.” See Archives of the Carmelite Monastery of Baltimore, Maryland (ACMB), II, 2.

- Antwerp Carmel, because of the long-term leadership of Anne of the Ascension (1619-44), had the influence of a motherhouse for the English and Dutch houses founded from it. Hoogstraet, however, had its own distinctive life and characteristics. It was founded in 1678 under the patronage of the Lady Rheingrave, Maria Gabriela de la Laing, Duchess of Hoogstraet, whose family exercised certain rights and duties and considerable influence in the life of the community during its one hundred sixteen years in the Flemish Lowlands. Every new member, before entering Carmel, was received at the Rheingrave Castle and frequently given her religious name by the Duchess. The family, moreover, played a central role in liturgical ceremonies and religious celebrations at the monastery. When the War of Succession broke out in 1701, the community, under the leadership of Mother Mary Teresa, Lady Rheingrave’s daughter, was moved for its safety to the Rheingrave Castle in Mechlin. It was eleven years before they returned from this exile to the Hoogstraet monastery.

- By way of example, we see that through Charles Neale’s mother, Ann Brooke, he and his nieces were related to the Boarmans. His grandmother, Ann Boarman, was the daughter of Major William Boarman (1630-1709), the progenitor of the Boarman family in Maryland who came to the colony about 1645. Two Boarmans, Matilda and Elizabeth, entered the community in 1799 and Mary Bradford, whose mother was a Boarman in 1802. Mary Ann Mudd was also related to the Boarmans. Moreover, a great uncle of Charles and Bernardina married Mary Jane Mudd, daughter of Captain James Mudd.

- Freedom of conscience was a value for the English Teresians for two reasons. Firstly, English Catholics had lived through long years of persecution in their homeland. Many Catholics in the Low Countries had forfeited property and wealth in England in order to practice their religion freely. Secondly, following the lead of Anne of Jesus (Lobera), Anne of the Ascension (Worsley) had struggled for the freedom to follow the Constitutions of Alcala, which she considered St. Teresa’s Constitutions for the nuns, rather than a later version approved for the Order. The Alcala Constitutions guaranteed the right of the nuns to choose their own confessors and Anne of the Ascension held on to this freedom for the English Teresians. Rather than change the Constitutions, she moved the Antwerp monastery from the jurisdiction of the Order to that of the Bishop of Antwerp.